“Yevgeny Matveev, mayor of the town of Dniprorudne within the area of Zaporizhzhia, was captured initially of the invasion as a result of he refused to cooperate with the Russian army. He was tortured and at last killed in captivity. At least his physique has been returned”. Nataliia Yashchuk is the Senior War Consequences Officer on the Centre for Civil Liberties, a Ukrainian human rights organisation and winner of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize. She rattles off a protracted listing of names and details about civilians and army personnel who’ve ended up in captivity in Russia and the occupied territories, together with Crimea.

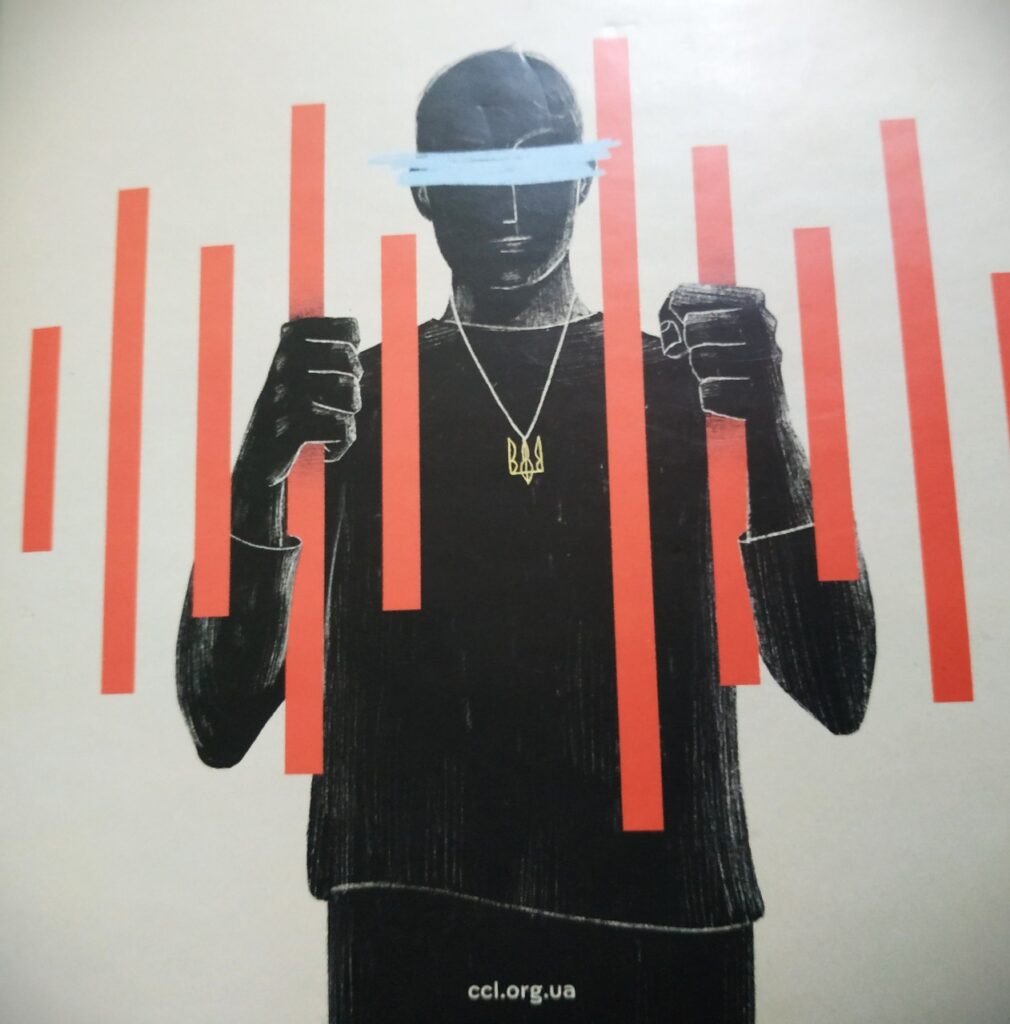

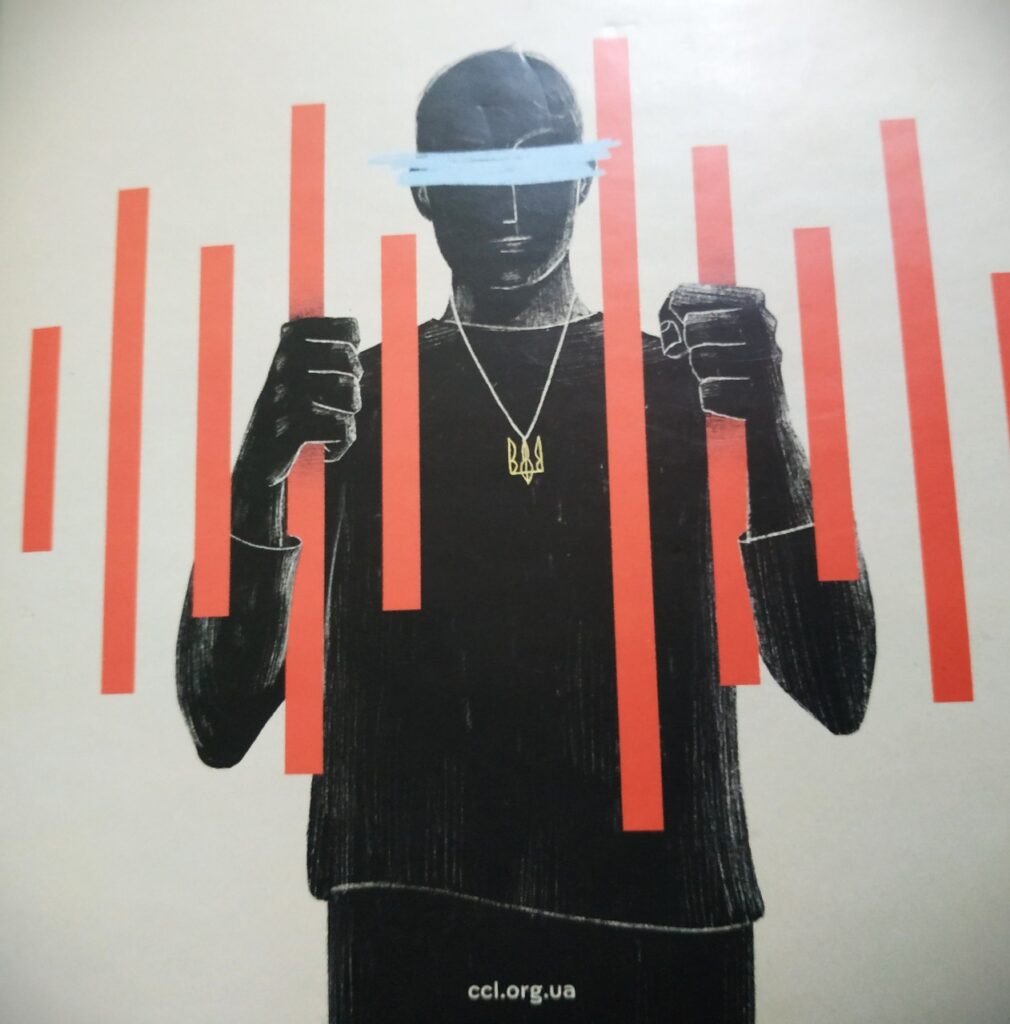

“Then there are whole households,” says Nataliia, pointing to pictures in a 2023 booklet entitled Prisoner’s Voice. “An individual with everlasting disabilities, a scholar, a workman, a pc scientist who fled the occupation in Crimea, a person who tried to avoid wasting his spouse, who died in his arms. Stories of all types. Andriy, Mykola, Serhiy…”

“Women too?” I ask timidly. “Women too. Iryna Horobtsova, a volunteer from Kherson: they took her away in entrance of her mother and father, stored her in solitary confinement, with out paperwork or data for over a 12 months. And then they constructed a pretend case in opposition to her, and convicted her, in keeping with their legal guidelines, as a spy”.

These are simply among the tales which have come to the eye of Yashchuk and the humanitarian staff who, like her, are concerned in human rights in one of the vital energetic associations in Ukraine. Most instances of imprisonment, explains Yashchuk, happen within the occupied territories, the place it’s estimated that round 16,000 individuals are illegally detained.

But the figures are approximate, as are these for kids kidnapped and deported. The newest instances contain households torn aside, civilians interrogated, detained, tortured after which maybe launched; others are transferred to unknown places and, after one or two years in captivity, convicted on trumped-up prices.

In addition to army personnel, there are civilian prisoners, residents who stay (or lived) in areas managed by the Kyiv authorities, kind of removed from the entrance line: Sumy, Chernihiv, Kharkiv, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia. But in addition they come from the area of Kyiv. “In the Kyiv oblast alone, in a month and a half of occupation, they kidnapped about 500 individuals,” provides Yashchuk, who, along with colleagues and volunteers, continues the search – the seek for prisoners, but in addition for justice”.

“This is probably the most documented warfare in human historical past,” says Oleksandra Matviichuk, director of the Centre for Civil Liberties. “We have in our database, which we’re conducting along with companions, greater than 88,000 episodes of warfare crimes. These should not simply numbers. Behind these numbers are particular human destinies”.

The nuances of political detention: civilians vs army personnel

In the present context of the Russian warfare in Ukraine, civilians and army personnel are detained in the identical circumstances, usually collectively, with none distinction. However, it is very important perceive that they don’t seem to be precisely a part of the identical class of political prisoners, which is basically based mostly on the authorized and institutional standing of the particular person on the time of detention, in addition to the context through which the deprivation of liberty happens (within the case of civilians, these could also be journalists, activists or demonstrators; and within the case of army personnel, these are members of the armed forces, safety forces or paramilitary forces).

This is one thing that the Russians themselves, the jailers, are likely to confuse, although on this case the confusion is deliberate.

“They are clearly all individuals who have been captured, immediately or not directly, in kind of complicated conditions,” explains Yashchuk. “The most troublesome state of affairs issues those that are arrested within the occupied areas after which held for lengthy durations with out clear cause, usually on critical and unjustified prices. This additionally applies to some army prisoners, who’re subjected to notably harsh circumstances. For comfort or simplification, we speak about ‘prisoners of warfare’ when referring to those that have been captured. But this time period actually solely applies to army personnel. Civilians can’t be thought-about prisoners of warfare as a result of they don’t seem to be combatants. These civilians are victims of kidnapping, arbitrary detention, unfounded authorized persecution and different abuses”.

Knowledge of the conditions confronted by civilians is often very restricted. Although some human rights organisations are engaged on their behalf, the size of the issue stays largely invisible. In Ukraine, the Association of Relatives of Political Prisoners of the Kremlin is an organisation that seeks to make clear the difficulty, along with organisations such because the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group (KHPG).

“There are two associated the explanation why civilians should not launched,” explains Maksym Kolesnikov, a former prisoner of warfare who has served within the Ukrainian armed forces since 2015. “Firstly, as a result of it will be tantamount to admitting a criminal offense. Secondly, they’re reluctant to attract contemporary consideration to those crimes”. Originally from Donetsk, Kolesnikov was captured on 20 March 2022 throughout the battle of Kyiv. After ten months in captivity, he was launched in a prisoner alternate in February 2023. According to his testimony, there have been over 500 detainees, each civilians and army personnel.

“At first they took us to Belarus, to a filtration camp, for about two days. From there, we had been taken to the town of Novozybkov, within the Russian area of Bryansk, to a preventive detention centre. The Russians move off Ukrainian civilians as army personnel: the Russian military merely makes them put on Ukrainian armed forces uniforms”, explains Kolesnikov, recalling that, in keeping with the foundations of warfare, civilians shouldn’t be captured as a result of they don’t seem to be army personnel, and this violates worldwide conventions.

The testimonies of those that return from Russian captivity

Physical and psychological trauma, difficulties in returning to “regular” life (if we are able to name it that in a rustic at warfare) and a scarcity of systematic help from the state: these are the challenges and obstacles confronted by those that have endured Russian prisons, confinement in darkish basements or cellars, and sometimes violence and torture. What awaits an individual after launch and what do they want, bodily, emotionally and legally? What function can society, communities and volunteers play?

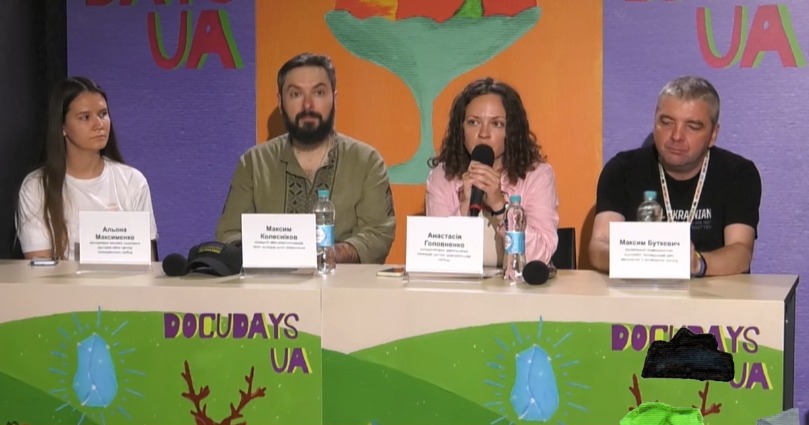

Kolesnikov and Maksym Butkevych, a Ukrainian human rights defender, journalist and civil society activist launched from Russian captivity in October 2024, sought to reply these questions throughout one of many conferences on human rights on the Docudays documentary movie competition.

“Combined medical and psychological help is important,” says Butkevych, after stating that the preliminary reintegration he underwent for 4 weeks in a rehabilitation centre for army personnel was crucial for him. A co-founder of the ZMINA Centre for Human Rights and Hromadske Radio, Butkevych enlisted as a volunteer within the Ukrainian armed forces in early March 2022. In July of the identical 12 months, he was captured by the Russian military and sentenced to 13 years in jail on trumped-up prices. He was launched in a prisoner of warfare alternate in October 2024.

‘Civilians can’t be thought-about prisoners of warfare as a result of they don’t seem to be combatants. These civilians are victims of kidnapping, arbitrary detention, unfounded authorized persecution and different abuses’ — Natalia Yashchuk

The most troublesome a part of rehabilitation, in keeping with Butkevych and Kolesnikov, is psychological help, particularly provided that many individuals consider they don’t want it. In addition, some additionally want social and authorized help, particularly if they arrive from occupied territories and have successfully misplaced the whole lot. “My rehabilitation lasted about three weeks: identification of issues, medical examination, exams, psychological exams,” explains Kolesnikov, who had misplaced 32 kilos in captivity.

When it involves rehabilitation and reintegration, whereas there’s a well-defined protocol for the army, there isn’t a such factor for civilians. “But it must be created!” insists Yashchuk. “Prosecutors and investigators should file the crimes dedicated and act in accordance with the Istanbul Convention. All this have to be completed by specialists, by specialists. And now we have them. But we’re effectively conscious that, given the present numbers and the numbers when extra return, we won’t have sufficient. The system must be strengthened”.

There are non-governmental organisations, foundations and spiritual organisations which are serving to. One of the targets achieved inside Ukraine is the modification of laws in order that civilians who’ve been launched are protected and can’t be mobilised. This is not any small achievement.

“However, right here too, a deep and structural downside emerges,” explains Yashchuk. “We are speaking about individuals who come primarily from the occupied areas. Their tales are very completely different: some managed to flee, some managed to pay a ransom for a member of the family, some had been launched in much less formal methods. But there’s one widespread component: they undergo all types of violence till they’re psychologically damaged. And when they’re utterly ‘destroyed’, if their captors have to receive one thing – a enterprise, a house, a car, any asset – they discover a solution to make them signal paperwork or hand over the whole lot they’ve in alternate for the promise of freedom. That particular person, now disadvantaged of the whole lot, usually makes the troublesome choice to return to Ukrainian-controlled territory. And right here a brand new ordeal begins: they can not show that they had been imprisoned, tortured or illegally detained. They haven’t any proof, no official data, nothing to show their expertise as a result of their identify doesn’t even seem on the “blacklists”. And those that may testify to this stay within the occupied areas. Thus, a vicious circle is created, and the state doesn’t but have a transparent, efficient process for recognising these invisible victims. This is a niche that we should fill. Because till there’s a system that recognises and protects these individuals, justice will stay incomplete, and the return to freedom will solely be partial”.

The European line on repatriated political prisoners

Alona Maksymenko, a colleague of Natalia Yashchuk, has helped spotlight the options wanted for the profitable reintegration of individuals coming back from captivity. First and foremost, fast entry to care and help: implementing and monitoring programmes that embrace medical and psychological help, doc acquisition and monetary help, with a specific give attention to households.

However, this have to be completed transparently and throughout the framework of clear legal guidelines and procedures. Some tips have been set out within the legislation on reintegration, adopted on 15 March 2024, which ought to guarantee a secure system to help the discharge and rights of freed prisoners.

Government authorities and establishments (ministries, commissions, authorities organisations) ought to work in good concord with civil society, every filling within the gaps to offer financial, authorized and social help.

An extra step ought to be taken by looking for worldwide help. Since the unlawful annexation of Crimea in 2014, the European Union has imposed financial and authorized sanctions to place stress on Russia within the context of the battle with Ukraine (18 packages of sanctions have been adopted to this point, the newest in July 2025).

These are undoubtedly key devices aimed toward bringing the Russian economic system to its knees and recognising its crime of aggression. In this regard, the creation of a Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression in opposition to Ukraine, introduced in 2023 and supported politically and financially by Brussels, goals to fill a niche left by the International Criminal Court, which can not prosecute Moscow for the crime of aggression attributable to jurisdictional limitations (Russia shouldn’t be a signatory of the Rome Statute). The tribunal is anticipated to be established by the tip of 2025 and will probably be tasked with judging the Russian political and army elite held liable for the warfare, reinforcing the no-impunity precept even for leaders of highly effective states.

According to Oleksandra Matviichuk, such an establishment is critical, and constitutes a political choice within the broadest sense: “If we wish to forestall wars sooner or later, we should punish the states and their leaders who begin these wars now. And this feels like widespread sense. But there was just one such precedent in your entire historical past of mankind: the Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals. […] But remind that the Nuremberg Tribunal is a court docket of the victors. That is, it tried Nazi warfare criminals after their regime had fallen. And as unhappy as it could be, such an unstated norm was set that justice is the privilege of the victors. But justice shouldn’t be a privilege. Justice is a fundamental human proper”.

Although it doesn’t immediately have an effect on the destiny of Ukrainian prisoners at present detained in Russia, this authorized instrument is a necessary first step in constructing a future framework of worldwide justice and accountability.

Indeed, whereas Brussels has taken motion in opposition to Moscow on this regard – albeit with restricted outcomes to this point attributable to systemic evasion, diversification in the direction of non-aligned companions and inside weak point in implementation – it is usually true that the precise affect of European initiatives supporting Kyiv, aimed particularly on the concern of repatriated political prisoners, which is never mentioned exterior Ukraine: at current, there are not any centralised, structured programmes guaranteeing direct entry to psychological or socio-economic help for these coming back from captivity. In the absence of such programmes, entry to those measures stays largely managed by Ukrainian nationwide actors, NGOs and humanitarian businesses, somewhat than by direct EU programmes.

Indeed, whereas Brussels has taken motion in opposition to Moscow on this regard – albeit with restricted outcomes so far attributable to systemic evasion, diversification towards non-aligned companions, and inside weaknesses in enforcement – it is usually true that the precise affect of European initiatives supporting Kyiv, notably on the difficulty of repatriated political prisoners, stays unclear. This concern receives little consideration even exterior Ukraine. Currently, there are not any centralized, structured applications making certain direct entry to psychological or socio-economic help for these coming back from captivity. In the absence of such measures, entry to help is essentially managed by Ukrainian nationwide actors, NGOs, and humanitarian businesses somewhat than direct EU programmes.

Political prisoners in Crimea

The Centre for Civil Liberties, along with different organisations, additionally offers with Ukrainian political prisoners in Crimea, notably Crimean Tatars. “Currently, there are greater than 200 instances associated to Crimea, the place residents are convicted for political causes. In addition, in addition they persecute the attorneys of Crimean Tatars, depriving them of their licences in order that they can not defend their very own individuals in Crimea”.

One of an important and high-profile instances is that of two attorneys, Lili Hemedži and Rustem Kamiljev, who had their licences revoked and had been then raided and subjected to intimidation. Their battle nonetheless continues to at the present time. They should not allowed to work or symbolize the pursuits of Crimean Tatars. They are continually persecuted.

The most infamous case of political imprisonment in Crimea is that of Nariman Dzhelyal, a journalist and political activist born in Navoiy, within the former Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, who returned to Crimea along with his mother and father in 1989. A contributor to the ATR tv channel and the Avdet newspaper, since 2013 he has been the primary vice-president of the Mejlis, the consultant physique of the Crimean Tatar individuals, and head of the Information and Analysis Unit. He was arrested on 4 September 2021 for the alleged “sabotage of a gasoline pipeline in Crimea, within the village of Perevalne”, and charged beneath Article 281, paragraph 2, of the Russian Criminal Code, which carries a jail sentence of between 10 and 20 years.

Unlike these of his colleagues, household and pals, Dzhelyal’s story has a cheerful ending. On 28 June 2024, Dzhelyal managed to return to Ukraine and final May was appointed by the Ukrainian president as ambassador to Turkey.

Prisoners in oblivion

The state of affairs of Ukrainian political prisoners, each civilian and army, stays dire: tens of hundreds of residents are detained in Russia and within the occupied territories, usually with none authorized recognition, accused of trumped-up prices comparable to terrorism or espionage and subjected to systematic torture in excessive detention centres comparable to Taganrog. The tragic loss of life of Ukrainian journalist Victoria Roshchyna in a Russian jail is testimony to the brutality of Moscow’s repressive system.

Denouncing these warfare crimes, securing the discharge of all political prisoners and offering concrete help to them and their households is, to say the least, obligatory. This might be achieved by protecting nationwide and worldwide consideration targeted on their state of affairs and pushing the European Union to determine concrete, focused and coordinated help programmes. Indeed, regardless of declarations of political help and funds allotted to Ukraine, the EU’s function within the concern of Ukrainian political prisoners stays marginal and poorly structured.

Brussels ought to take into account unanimously and extra actively selling the creation of a global monitoring mechanism on detention circumstances, supporting reintegration and rehabilitation programmes for returned prisoners with devoted funds, and pushing for the introduction and implementation of focused sanctions in opposition to Russian officers concerned in arbitrary detentions. Furthermore, a coordinated EU diplomatic initiative may assist strengthen multilateral stress on Russia to make sure respect for human rights. Countries comparable to Poland and the Netherlands, that are among the many essential promoters of European resolutions on the popularity of Russian duty for warfare crimes, illustrate how a sustained dedication, each at nationwide and European degree, can foster the event of important devices.

When it involves the difficulty of such prisoners, the European political agenda must be extra concrete and visual, and never merely symbolic.