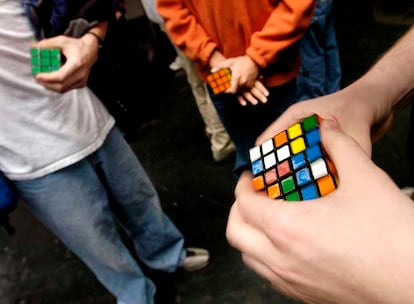

“This,” says Alexey Pajitnov, whereas holding a scrambled Rubik’s Cube, “is my favourite puzzle. But I additionally suppose it’s merely the most effective issues humanity has ever invented. If we may solely ship 10 issues into area, this ought to be considered one of them.”

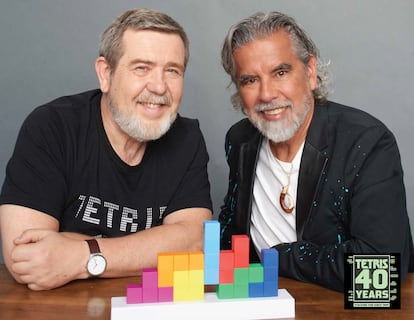

Standing beside Pajitnov — who revolutionized the digital world when he created Tetris, the best-selling online game of all time — is the dice’s creator, Ernő Rubik, smiling broadly.

Both males hardly ever give interviews, however they agreed to talk with EL PAÍS on the OXO Video Game Museum in Málaga, Spain. Rubik — who spends half the yr in San Pedro de Alcántara, a resort city in Málaga province — visited the museum on Friday, December 5. The following day, on this temple of artistic leisure — which is at all times filled with kids — Pajitnov acquired an honorary award.

The dialog is a tectonic conflict between two minds that know the best way to mix leisure, creativity and mathematical challenges. With one distinction, in fact: you may’t get extra analog than a Rubik’s Cube… and you’ll’t get extra digital than Tetris.

The assembly begins with every of them reminiscing about how they found the opposite’s creation: “I spent two months attempting to unravel it. And I did it with none assist. It’s one of many best achievements of my life,” Pajitnov confesses, laughing.

And Rubik? How did he uncover Tetris?

The dice’s creator returns the praise: “When we launched the dice in Hungary, again in 1974, it was an enormous success, however clearly, many issues didn’t attain my nation, which was behind the Iron Curtain,” he explains. “The dice’s success allowed me to journey, purchase computer systems and entry many issues that had been offered within the West. I’m not that a lot of a digital particular person, however I like geometry; I noticed Tetris’s potential as quickly as I laid eyes on the sport throughout a visit to New York.”

Some think about Tetris and the Rubik’s Cube to be video games. Some see them as mathematical challenges, whereas others marvel at their design, class and ease. But past their performance, these innovations have undoubtedly had a decisive affect on tradition and society within the final half-century.

Rubik — an 81-year-old architect born in Budapest — invented the 9×9, six-colored dice in 1974. He initially designed it as a instructing software to elucidate three-dimensional ideas to his college students. In 1980, the Ideal Toy Company marketed it internationally underneath the identify everyone knows it by: Rubik’s Cube. And, since then, it has grow to be a worldwide phenomenon, as a consequence of its simplicity, accessibility and, in fact, the psychological problem that it gives. It’s unimaginable to calculate what number of cubes (or knock-offs) have been offered, however the variety of trademarked cubes alone is estimated at practically 500 million.

Tetris, in the meantime, was created by Pajitnov, who was born in Moscow 70 years in the past. In 1984, he constructed the sport on an Elektronika 60 pc. He designed it as a puzzle based mostly on falling geometric items that should kind full traces. Its worldwide enlargement started in 1988, when a number of firms past the Iron Curtain purchased the license for the sport. Its reputation subsequently skyrocketed after being included with the Game Boy handheld console in 1989, together with the discharge of different handheld units particularly designed to play it. Since then, it has been tailored to dozens of platforms, turning into a common basic of video video games, with a whole lot of variations (and rip-offs, in fact), together with variations to all types of units and its leap into digital actuality.

With a whole lot of thousands and thousands of copies offered, Pajitnov didn’t initially obtain royalties for the sport, as these belonged to his employer: the federal government of the then-Soviet Union. He solely started to acquire copyrights in 1996, when he and Henk Rogers fashioned The Tetris Company (TTC). Rogers — who joined Pájitnov in Málaga — walks by way of the halls of the OXO Museum whereas the interview takes place, pausing to gaze on the units on show.

Both creations — the Rubik’s Cube and Tetris — are the epitome of mechanical class, in addition to an indication of how easy artifacts can comprise extremely complicated and enjoyable dynamics. They’re like musical scores, able to be reinterpreted by new generations.

“Looking again now,” Pajitnov displays, “if there’s one factor I believe I might be pleased with, it’s that the sport helped convey folks nearer to computer systems. Back then, these units had been critical issues — considerably disagreeable — they usually commanded a variety of respect. And, out of the blue, there was a quite simple, very accessible sport that individuals may work together with on a pc.”

A cognitive problem within the age of comfort

There’s one phrase that each inventors use enthusiastically of their dialog with EL PAÍS: “problem.” In a time when the overwhelming majority of content material consumption is passive — reels, foolish movies, collection watched within the background, and even information tales that finish with the headline — it’s price remembering that these two units challenged folks: they pushed them to think twice, to be able to full the problem they introduced.

“Of course! My greatest concern at present is synthetic intelligence,” says Pajitnov. “It’s making folks not suppose, not face challenges. The leisure that challenges us is the type that we have to hunt down,” he argues, pointing to the dice on the desk in entrance of him.

“We’ll need to see if AI ever turns into as clever as us,” Rubik provides, “however progress at all times has contradictions: a car’s elevated velocity helps us get locations sooner, however it additionally makes accidents extra critical. Everything has optimistic and damaging results.”

“You get your candy, however you get to pay!” Pajitnov exclaims.

Rubik elaborates: “AI appears to have come to beat nature. Well, that’s unimaginable. What we have now to make sure isn’t that AI is healthier than us, however slightly that this technological revolution supplies options to our issues. It’s that easy.”

“And that it helps us suppose no more individually, however as a society,” Pajitnov provides.

“You have to find what’s finest about your thought,” Rubik displays. “And looking for the proper answer is difficult: nearly the whole lot might be refined and improved. The best discovery, actually, is pointing to a route: stating the place we ought to be heading. Trying to instill a mindset in folks that motivates them to realize large targets.”

When requested what’s the strangest scenario through which they’ve seen somebody taking part in Tetris or attempting to unravel a Rubik’s Cube, Pajitnov has a transparent reply: “Many heads of IT firms have confessed to me that they used to put in viruses on their staff’ computer systems to delete Tetris in the event that they put in it,” he laughs.

And what would they are saying to a younger artistic who has to navigate this unsure twenty first century? “The solely recommendation I may give is to hearken to your self. Never take note of what advertising or developments let you know. Look for what makes you cheerful,” Pajitnov says with conviction.

For his half, Rubik has two items of recommendation: “First: be curious.” Throughout the dialog, Rubik has extolled the innate, nearly childlike curiosity that — in response to him — ought to information human habits. “And second, by no means surrender once you’re going through a major problem. If you may’t remedy it, maybe it has no answer, however for those who deal with it, chances are you’ll notice you could enhance sufficient to unravel it.”

Such a lesson couldn’t be higher crystallized than in these two artifacts. Tetris and the Rubik’s Cube — kings of the digital and analog worlds respectively — will certainly proceed to entertain (and problem) folks for a lot of many years to come back.

Sign up for our weekly publication to get extra English-language information protection from EL PAÍS USA Edition