There might be few students working wherever on this planet at the moment with Partha Chatterjee’s sustained report of shut mental engagement with India’s political economic system and its place within the colonial and postcolonial worlds. As is well-known, his pursuits additionally vary extensively over points in social and cultural historical past, from rural mentalities to bourgeois types of spiritual perception, from the function of discourse in shaping the instruments of presidency and legislation, to the survival methods of the poor excluded from the advantages of market reforms.

His pursuits have additionally been strongly comparative, together with compelling accounts of the technocratic detachment of recent postcolonial states from what he calls the “people-nation”, the good mass of their citizenry. “Political society” emerges to fill the house: an area for political contestation during which their enormous populations of city poor are in a position to search rights and recognition outdoors formal state establishments. A number one voice of scholarly reflection and critique, a lot of his current work explores the expansion of populist assist for types of strong-man rule in India and internationally.

Federal futures?

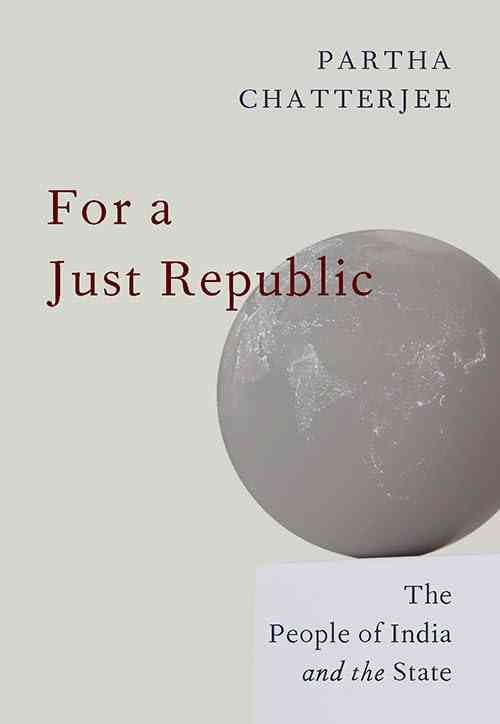

Chatterjee’s new guide, For a Just Republic: The People of India and the State, affords a essential exploration of the subcontinent’s historical past because the Nineteen Thirties that’s by turns fine-grained and wide-ranging. Naturally, he revisits many key arguments from his earlier work, usually with sharp new insights. What is novel in regards to the guide, although, and more likely to provoke vast debate, is his straight posed query. What may represent “justice” at every degree of the federal republic’s politics and society, and – maybe much more importantly – what social forces may be capable to carry it about?

To construction the guide, Chatterjee employs his acquainted distinction between India as a nation-state and what he calls “the people-nation”. The latter is the area of neighborhood, native id, attachment to put and above all a shared vernacular language. A “simply republic” requires correct recognition for “the people-nation” inside India’s federal construction. This means appreciating that India’s vernacular language communities possess a deep historical past and sense of their very own distinctive territorial homelands. Independent India’s linguistic states emerged out of this long-term strategy of cultural formation.

Having laid out this broad problematic, Chatterjee reminds us of the federal mannequin that got here out of the Constituent Assembly Debates. The mannequin emphasised nationwide unity, a single nationwide economic system, a largely presidential fashion of politics, and the disruptive potential of widespread sovereignty. The solely actual respite, Chatterjee suggests, got here with the coalitional democracy that flourished between 1989 and 2014. He concedes that India’s expertise of coalition politics has been a chequered one. But solely a federal kind primarily based on coalition politics can accommodate shifting social forces, permit every state to retain its distinctive id, and, above all, forestall any area from imposing its will on the others.

Concise and stuffed with contemporary insights, the primary 4 chapters of the guide reprise a few of Chatterjee’s most necessary arguments. He explores the long-term limits of liberal governmentality within the Indian setting, and the succession of “passive revolutions” by means of which Indian capitalism has been in a position to exploit its altering political setting since 1947. He explores its contested hegemony underneath Modi and the deeply unstable authorized framework for Indian citizenship.

Chatterjee strikes in his fifth chapter to the actual coronary heart of the guide. Given India’s social complexity, various and nonetheless rising regional states, lopsided financial improvement and contrasting cultures of capitalist improvement, how can or not it’s doable to agree on any definition of justice as the premise for a “simply republic”? In this rigorously argued a part of the guide, Chatterjee emphasises – maybe not surprisingly – a comparative and contextual strategy. Different rationalities could form what individuals worth. Collective in addition to particular person rights matter for oppressed communities, and it’s troublesome all over the place to mix procedural equity with substantive justice.

But the issue, he factors out, runs far wider than balancing consistency with the undoubted must ship protections to the precarious and sometimes immiserated staff who populate India’s enormous casual economic system. It can also be the long-term decline of belief in India’s ponderous authorized equipment. There can also be the widespread widespread perception {that a} single righteous chief could also be extra more likely to ship significant justice, and that authoritarian rule could higher assure actual social upliftment. Whilst acknowledging the undoubted attraction of those siren calls, Chatterjee factors us reasonably in direction of the lengthy, gradual work of political training in defence of democracy.

He then strikes on, within the second half of the guide, to India’s “people-nation” itself, and to the coalitional democracy he sees as almost certainly to ship these finely balanced political and judicial compromises. He factors out a key improvement in India’s federal construction. Linguistic states and the rise of regional events have created what’s now an “uneven” federal system. It recognises range and the necessity for native lodging, and therefore supplies one thing of a bulwark in opposition to regional secessionist actions.

A federation of ‘peoples’?

But Chatterjee brings a particular new dimension to this now acquainted argument. He references the historian Christopher Bayly’s well-known rivalry that early fashionable India noticed the emergence of “regional patriotisms” grounded in the end in vernacular language communities. These patriotisms gained a dramatically expanded cultural attain with the approaching of vernacular print. Out of those processes, Chatterjee contends, India has now emerged very a lot as a federation of “peoples”. The nation itself is now imagined principally within the language of regional vernaculars, every understood to own its personal distinctive historical past and tradition.

He concedes, after all, that many components formed patterns of linguistic unification and the demand for impartial statehood. These embody perceptions of drawback by linguistic minorities, fears of domination by neighbouring language communities, issues to guard entry to pure sources, and perceptions of political celebration benefit. The energy of language additionally performed its half, enabling in any other case fairly heterogeneous populations to recognise themselves as sharing a typical historical past and membership of a language neighborhood.

Nonetheless, the very make-up of linguistically constituted states offers a few of them a particular function. All have come into existence by means of political negotiation and compromise. They have expertise in managing social range and containing its social strains by seeking to commonalities of historical past and tradition. Many have a protracted report of negotiating particular provisions to take account of specific native wants and circumstances.

Given these qualities, Chatterjee suggests, a key function for a few of them lies in supporting a revival of the coalitional type of nationwide politics, and thru it, of pushing again in opposition to the Hindu majoritarianism that has its principal residence within the Hindi states. It was solely in these states {that a} language neighborhood arose on the premise of spiritual tradition, as communities of Hindi audio system emerged from the mid-nineteenth century on the premise of a newly mobilised Hindu spiritual id. This offers the Hindi states a really completely different character from the linguistically constituted states, the place very step by step growing commonalities of vernacular language drew in in any other case culturally various communities.

Faced with this spiritual majoritarianism, Chatterjee asks, how are the rights of Dalits and Muslims throughout India to be safeguarded in a “simply republic”? He reminds us of Ambedkar’s deep frustration on the thwarting of widespread sovereignty in the course of the strategy of constitution-making. Following Ambedkar, he insists that it’s the collective, not the person, that issues when the rights and freedoms of minority teams are at difficulty. But what in regards to the emergence of profitable elites inside these teams, whose declare to particular protections could appear a lot much less robust? The precept of widespread sovereignty signifies that solutions should come from inside Dalit and Muslim communities themselves, and replicate their collective autonomy and drive for self-representation.

Turning to the dynamics of sophistication energy because it has developed throughout India’s federal construction, Chatterjee outlines the very completely different histories of the linguistically constituted states. In some states of India’s “core development” zone – Maharashtra, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu – robust regional identities and rights-based interventions to assist the marginalised have considerably boosted human improvement indices. Key strikes have been the democratisation of healthcare and training, larger widespread involvement in public companies and transport subsidies. The social base of entrepreneurship in these states tends to be broad, technically expert labour comes from all castes and lessons, and there’s a productivist social ethic which favours the emergence of SMEs.

“Zones of extraction”, corresponding to Chattisgarh, in contrast, concentrate on the export of uncooked supplies and commodities. They lack a powerful regional id or cohesive caste construction, and native Maoist actions lack attraction outdoors their core Adivasi supporters. Different once more are “zones of labour provide” corresponding to West Bengal. These have seen large-scale outflows of staff in addition to capital, as successive state governments have prioritised safety of the peasant subsistence economic system. Many small-scale enterprises flourish, however with out the cohesion of a bigger entrepreneurial class or a wider political drive to rework healthcare and training.

For Chatterjee, subsequently, the progressive capitalist tradition and distinctive social ethic of key states inside India’s core development zone have a particular historic significance. Their shared deep roots in a typical historical past and vernacular language, their acceptance of range as a energy reasonably than a weak point, and their historical past of inclusive community-building will give them a key function in constructing the “simply republic”. And, after all, these are the states almost certainly to have interaction constructively in coalition-building, and therefore to face most successfully in opposition to Hindu majoritarianism.

In conclusion, Chatterjee turns to gender, caste and sophistication. The most profitable actions for gender justice haven’t emerged from any pursuit of common norms, however reasonably from motion in girls’s personal quick lives. The nice mobilisation of OBC and Dalit communities because the Eighties, and the massive disparities of wealth which have emerged within the “billionaire’s raj” of Modi’s India, imply that older catch-all classes should give approach right here too. The greatest hope of assembling progressive caste and sophistication alliances in assist of the “simply republic” will come from a concentrate on regional and native caste-class formations, notably within the “core development” areas with their distinctive native capitalist cultures.

Some questions

It is testimony to the analytical sharpness and provocative framing of Chatterjee’s work that few readers will come away with out additional questions. As is well-known, Bayly’s work on “regional patriotisms” and vernacular print drew considerably on Benedict Anderson’s influential 1983 work, Imagined Communities. For Anderson, along with his insistence on the hyperlink between capitalism and print tradition, the emergence of vernacular print was a profoundly repressive, in addition to a inventive course of. Some vernacular languages grew to become “languages of energy” of their elevation to print. Others, primarily based in oral custom alone, with scripts deemed unsuitable for print, or disapproved for his or her affiliation with “uncultured” communities, have been pushed to the margins. What may this inform us in regards to the cultural cohesion of linguistically constituted states?

Nor does Chatterjee’s mannequin suggest methods of participating constructively with the Hindi states, of connecting with their enormous populations of city poor, and others who could also be drawn away from a majoritarian consensus. This obvious conceding of such a key political floor appears puzzling, as a result of Chatterjee has elsewhere written so eloquently about these populations and their dynamic histories of political contestation outdoors formal state constructions. North India additionally, after all, has a wealthy and persevering with historical past of heterodox spiritual tradition during which syncretism and bhakti-related social inclusiveness have performed a big function. Again, it could be fascinating to have Chatterjee’s additional reflections on this a part of his argument.

Needless to say, these are very minor issues, positioned alongside the dimensions of Chatterjee’s outstanding achievement on this work. It combines enormous breadth, putting analytical sharpness and a sustained concentrate on a fully key query within the politics of recent India and federal states internationally. In the current second, it’s a guide that students and the intense common reader alike will wish to attain for and to learn.

Rosalind O’Hanlon is Professor Emeritus of Indian History and Culture on the University of Oxford and a Fellow of the British Academy. Her newest guide is Lineages of Brahman Power: Caste, Family, and the State in Western India 1600–1900. Her earlier books embody Religious Cultures in Early Modern India: New Perspectives, coedited with David Washbrook, and At the Edges of Empire: Essays within the Social and Intellectual History of India.

For a Just Republic: The People of India and the State, Partha Chatterjee, Permanent Black and Ashoka University.